Before you bite into that beautiful tomato in your garden, the tomato fruitworm, or the Colorado potato beetle, might have beat you to it.

At the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), researchers explained how microbes inside the gut of insects turn off the ability of the plant to defend itself against chewing insects. New science suggests microbes could also be used to turn those defenses back on—a potential solution to a major pest problem.

The Pests & the Plants They Eat

The tomato fruitworm (Helicoverpa zea) is a devastating agricultural pest in North and South America. With a voracious, diverse appetite, the worm counts more than 100 different crops as food. Also known as the corn earworm and cotton bollworm, tomato fruitworms consume leaves and stalks of the plants, and prefer green tomatoes, which are often attacked by fungus after entry of the worm.

Native to Mexico, the Colorado potato beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) causes extensive damage across the US, Asia, and Europe. Like the tomato fruitworm, the Colorado potato beetle strips the leaves of plants, which include members of the nightshade family (Solanaceae) such as potatoes, tomatoes, eggplants, and peppers, among others.

Because these insects are becoming resistant to the pesticides used to control them, new science is needed to understand, and disrupt, their damage to important food crops. Andrei Alyokhin, a professor of applied entomology at the University of Maine, told Invisiverse, "Generally speaking, commercial potato production is impossible without beetle control. So, losses could be up to the entire value of the US commercial potato crop, which is about US $4.2 billion per year."

While it looks like these, and other insect pests, simply land on a plant and start to nosh, it is not that simple. The entire environment in which a plant grows, or an insect feeds, is called a phytobiome. Within the phytobiome are microbes, some that live as symbionts inside the insects that feed on plants. Symbionts live closely with or within a host. Symbiont relations could be, but are not necessarily, mutually beneficially.

Gut Bacteria Confuse Plants Trying to Stop Chewing Insects

Because plants cannot pull up roots and move on if they are attacked by an insect, they defend themselves when attacked in several ways. Plants use spines, thorns, poison, and other chemical remedies to defend themselves and warn neighbors of potential onslaught.

In research presented at the AAAS meeting, Gary Felton, a professor and department head of entomology at Pennsylvania State University, discussed the microbial interaction between insect pests, their gut bacteria, and the reaction of plants when under the influence of microbes. The discussion culminates several years of research by the Penn State group to uncover microbial signaling mechanisms on tomato and other plants. Here are some of their findings:

1. Plants Defend, Microbes Defeat

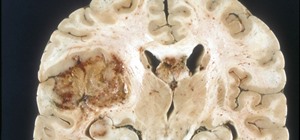

In research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2013, Felton and his research team used scanning electron microscopy to identify bacteria left by Colorado potato beetles on chewed plant leaves. The bacteria was deposited through saliva or regurgitation onto the tomato plant leaves.

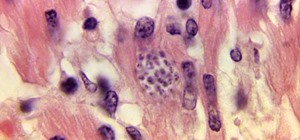

When a chewing insect (an herbivore) puts the bite on a tomato leaf, the plant immediately detects the mechanical damage and uses plant hormones, called phytohormones, to trigger the plant's defenses. Plant defense takes the form of secreting jasmonic acid (JA), which interrupts the digestion of the chewing insect, probably something like a fast-acting stomach ache.

If the attacker is a microbe, like a bacteria or fungi, the plant responds to the attack by secreting salicylic acid (SA), which creates proteins to attack the outer protective layers, called cell walls, of the invading microbe. These proteins also communicate and prepare nearby plant cells for impending attack and defense.

To respond effectively to each assailant, plants must communicate clearly to deter damage. When the gut bacteria of chewing insects is detected by a plant, the plants might confuse chewing damage for microbe invasion and use the wrong defensive weapon.

This study found the gut bacteria from the Colorado potato beetle created negative "cross-talk" as plants tried to defend against the chewing damage. Instead, tomato plants respond to the deception of microbes on its wounded leaves. The effect is that plants are deceived into turning off defense to the chewing damage, instead defending against microbial damage that is not taking place. The term for this type of miscommunication is called "JA-SA antagonism."

2. Insect Gut Bacteria Deception Impacts Different Plants

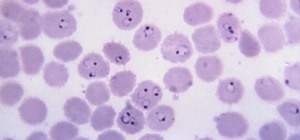

In a study from the same research group published in Nature in January 2017, the team explored other host plants for the same reaction to the gut bacteria from the Colorado potato beetle.

Experimenting with cultivated and wild host plants including potato, tomato, eggplant, nightshade, horsenettle, and buffalobur plants, study authors write that "JA-SA antagonism is present in Solanum plants, and thus may be exploited by herbivores and their symbiotic bacteria."

The amount and type of bacteria used to suppress the defenses of plants differed, depending on the type of plant being attacked. Bacterial communities living in the gut of insect hosts respond to the nutrient and material composition of food taken in by the chewing insect.

What About Tomato Fruitworms?

Researchers explored how this process works with tomato fruitworms. In a study published in New Phytologist in February 2017, Felton and his team observed gut bacteria enhanced the ability of the tomato fruitworm to deposit bacteria-laden saliva on the tomato leaves. Unlike Colorado potato beetles, tomato fruitworms apparently do not regurgitate on their food very often, requiring higher amounts of saliva to trigger a misfire in the plant's defenses.

In addition to confounding the defense mechanisms of target plants, researchers suggest gut bacteria serve insect hosts through promoting growth, aiding digestion, detoxifying potential plant poisons, and deterring plant-produced proteins that could otherwise damage the insect.

Better understanding of how gut bacteria, insects, and plants interact could provide key information for development of better crop defenses against these herbivore pests.

"When we know more about all these microbe, herbivore, and plant interactions, we may be able to manipulate the system to make the plants manipulate the bacteria," Felton said in a press release. "Probiotics (mixes of specific bacteria or viruses) could alter the gut microbiome to benefit the plant."

There is no perfect remedy for Colorado potato beetles or tomato fruitworms. For either, integrated pest management techniques are important. For the home grower, crop rotation is key. Your hard work will pay off in beating the beetles and the worms to the first bite of your next homegrown tomato.

Just updated your iPhone? You'll find new emoji, enhanced security, podcast transcripts, Apple Cash virtual numbers, and other useful features. There are even new additions hidden within Safari. Find out what's new and changed on your iPhone with the iOS 17.4 update.

Be the First to Comment

Share Your Thoughts